King Records' Syd Nathan was decades ahead of the competition

By Bruce Sylvester

The 1940s was a watershed decade for new indie labels such Chess, Imperial, Aladdin and future majors Capitol, Atlantic and Mercury. But King Records ruled the indie circuit, thanks largely to the prescience of its controversial founder and owner Syd Nathan, who understood how to bridge the gap between black and white music, as Sam Phillips would a decade later at Sun.

King’s doo-wop acts included Billy Ward & His Dominoes (where lead singers Clyde McPhatter and later Jackie Wilson began their recording careers), Hank Ballard & The Midnighters, The “5” Royales, Otis Williams & His Charms, the early Platters and, late in their career, The Five Keys. James Brown, Freddy King, Johnny “Guitar” Watson, Lonnie Johnson, Bull Moose Jackson, Wynonie Harris, Roy Brown, Little Willie John, young La Vern Baker and Joe Tex were among the label’s R&B, jump blues and blues acts. The country roster included The Stanley Brothers, Reno & Smiley, The Delmore Brothers and, in their early days, Merle Travis and Homer & Jethro.

King and its various imprints— Queen, Federal and De Luxe — provided subsequent artists with songs galore. The Shirelles’ and then The Mamas & The Papas’ “Dedicated To The One I Love” was first done by The “5” Royales. Peggy Lee’s signature song, “Fever,” came from a 1956 Little Willie John disc. Freddy King provided Eric Clapton with “Hide Away” and “Have You Ever Loved A Woman.” Sonny Thompson’s “I’ll Drown In My Tears” (penned by King producer Henry Glover) morphed into Ray Charles’ 1956 “Drown In My Own Tears.” Tiny Bradshaw’s “Train Kept A-Rollin’” has been redone by Johnny Burnette, The Yardbirds and Aerosmith (whose “Big Ten Inch Record” came from a 1952 Jackson disc). Roy Brown’s (and then Harris’) “Good Rockin’ Tonight” became an anthem in the hands of young Elvis Presley at Sun.

(Learn more about R&B music with "The Big Book of Rhythm and Blues")

King was founded in Cincinnati in 1943. Talkative and curious, record store owner Nathan would ask his customers — often Appalachian migrants from across The Ohio River — why they liked certain discs, and he decided to could start a country label. Its earliest pressings (from a Louisville, Ky., plant) were so badly done that they resembled soup bowls to him. Then Cincinnati’s only pressing plant found him so obnoxious that he was banned from its premises. So he built his own plant, which fit his belief that his young label should handle all of its functions, including cover art and national distribution, rather than contract out tasks.

Thrifty and practical, Nathan realized that if he put out another style of music — black music — his distributors could increase their total sales in a city. His initial idea was that his new imprint, Queen, (Cincinnati being known as The Queen City) would feature race records. Founded in 1945, Queen signed big-band veterans Jackson and Earl Bostic plus the stunning gospel Swan Silvertone Singers. Instead of always recording from scratch, he often bought masters from independent producers, such as J. Mayo Williams (who’d accomplished so much for Paramount and Vocalion in earlier decades). In 1947, Nathan abandoned Queen, putting its artists on King.

That year, Nathan also bought a majority interest in New Jersey-based De Luxe Records, whose Roy Brown had recently recorded his own composition, “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” since he hadn’t yet convinced jump blues champ Harris to sing it. Then, in late 1947, the libidinous Harris signed with King after what Nathan described as a late-night negotiation session in a hotel room where Harris was wearing nothing but pink satin underwear in the presence of three naked women. The public proved very ready to hear Harris intone, “I heard the news, there’s good rockin’ tonight,” on his debut King platter, and the success enabled the label to move further into doo-wop, gospel and blues.

With its shifting vocal leads, falsetto swoops and deep-bass rumbles, gospel harmonizing was, of course, the bedrock of doo-wop. Prior to jumping to King, The “5” Royales had sung gospel as The Royal Sons Quintet. The original Dominoes’ McPhatter and Charlie White came from Harlem’s Mount Lebanon Singers. Singing doo-wop, their ecstasy was sensual, not sacred.

In 1950, The Dominoes became the first act on King’s Federal imprint, a label for recordings helmed by King’s new producer, Ralph Bass, whom Nathan had lured away from smaller rival Savoy. Freddy King, The Midnighters and sultry teenager Little Esther (the future Esther Phillips) subsequently recorded on Federal.

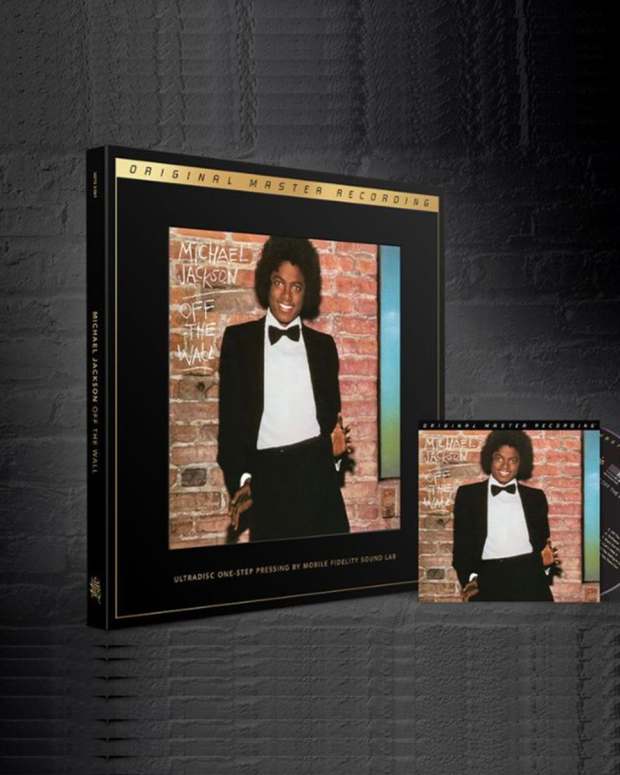

Syd Natha, founder of King Records. Copyright 2011 Gusto Records, Inc., owner of the King Records catalog, Nashville, Tenn.

A seminal group in the evolution of black music, Billy Ward & The Dominoes was the brainchild of Billy Ward, a preacher’s son, Juilliard School alumni and former boxer. He ran his group with the discipline he’d learned in the Army — and drove his poorly paid singers out of it. They received a flat salary rather than a share of royalties their records earned. Ward didn’t even perform with them. While the soaring tenor of a teenage McPhatter propelled “Have Mercy Baby” to No. 1 on the R&B charts, the group’s most-noted song over the decades relied on bass Bill Brown’s character Lovin’ Dan in sexually swaggering “Sixty Minute Man.” That song’s success inevitably led to a comic follow-up — Dan’s amatory exhaustion in “Can’t Do Sixty No More”) — and attempt at cloning with “Pedal Pushin’ Papa,” where references to Gene Autry and Fred Astaire show how much white entertainers were reaching black audiences. Incidentally, the bridge in The Dominoes’ 1952 “That’s What You’re Doing To Me” was blatantly copied in The Moonglows’ 1954 smash “Sincerely” on Chess.

Lovin’ Dan was one of King songs’ countless raunchy characters, along with Pete “Guitar” Lewis’ “Chocolate Pork Chop Man” and Roy Brown’s “Butcher Pete.” Little Esther had to arm herself against a lecherous man of the cloth on “The Deacon Moves In” with The Dominoes. Jackson sang “I Want A Bow-Legged Woman,” and Dorothy Ellis offered “Drill Daddy Drill.” Dave Bartholomew’s playful “My Ding-A-Ling” was adapted by Chuck Berry on Chess. In the 1970s, Maria Muldaur jazzed up The Swallows’ laid-back 1951 “It Ain’t The Meat (It’s The Motion).” Unstoppable Harris sang “Shake That Thing,” “Lovin’ Machine,” “Sittin’ On It All The Time,” “I Like My Baby’s Puddin’” and “I Want My Fanny Brown.” The symbolism in his “Keep On Churnin’” is especially salacious. King’s catalog was far raunchier than, say, that of its competitor, Atlantic. A robust five-CD “Risque Blues” series preserves it today.

And then, there were The Midnighters’ notorious Annie songs: “Work With Me, Annie,” “Annie Had A Baby” and “Annie’s Aunt Fanny.” Etta James’ breakthrough as a teenager, “The Wallflower (Roll With Me Henry),” on Modern was an answer song, with Henry being Midnighters’ vocalist Hank Ballard. Like Lovin’ Dan, even Henry eventually wore out on the series’ finale, “Henry’s Got Flat Feet (Can’t Dance No More).”

Besides answer songs and sequels, King — like other labels of its day — got plenty of mileage from covers. The Dominoes redid Tony Bennett’s “Rags To Riches” and “Over The Rainbow” from “The Wizard Of Oz.”

After bailing out of The Dominoes, Charlie White and Bill Brown formed The Checkers and sang an impressive, upbeat take on World War II era “White Cliffs Of Dover.” Covering another black act, The Charms snared the race market on 1954’s “Hearts Of Stone” by having a more professionally engineered and better-distributed single than The Jewels’ even more interesting original on the tiny R And B label.

Because Nathan’s publishing companies owned the rights to many songs on King, he would have black acts cover his white country songs and vice versa. Harris’ hit “Bloodshot Eyes” came from Hank Penney. Jackson’s “Why Don’t You Haul Off And Love Me” was penned by King’s Wayne Raney. The gambit sometimes succeeded, but it took on elements of the absurd in 1960 when Nathan had The Stanley Brothers bluegrassified Ballard’s “Finger Poppin’ Time.” By and large, King’s black acts did better covering its country songs than its white singers did with the doo-wop and R&B songs.

For political or artistic reasons or both, Nathan liked to shake things up by having white Ralph Bass and black Henry Glover produce acts of the opposite color. A Jew, Nathan had experienced anti-Semitism and wanted to curb prejudice in general. His company’s job application form asked would-be employees if they would object to working with someone of a different race, nationality or religion. Believing that prejudice can be rooted in fear of the unknown, Nathan sometimes hired people who’d answered yes. Why? He thought that they might overcome their prejudices by being around members of other groups. The company was a color-blind meritocracy that was years ahead of its time in 1940s-’50s Cincinnati.

Nathan was an interesting character study. He was obese and myopic and had high blood pressure. His formal education had ended with the ninth grade (“I couldn’t see, so why bother.”) When the payola scandal rocked the music industry in 1959, he said, of course, he’d paid it and he had the checks to prove it. Without the checks, the payola wouldn’t have been a verifiable tax deduction.

Ralph Stanley has said that Nathan was profane and repeatedly broke wind but (can we overlook “Finger Poppin’ Time”?) he rarely interfered with The Stanley Brothers in the recording studio. On the other hand, Freddy King was disturbed by the tacky titles Nathan stuck on his instrumentals. Tight-fisted Nathan saw himself as a bit of a percussionist. After McPhatter unhappily departed from The Dominoes — whether he quit or was fired depends on who’s telling the story— Atlantic Records recruited him to form The Drifters to sing behind him, and he told company co-founder Ahmet Ertegun, “I hope you’re not going to play drums on my sessions.”

As Jon Hartley Fox wrote in his laudable King history “King Of The Queen City” (University Of Illinois Press, 2009), “Nathan was an intelligent, complex and unusual man, a guy who could get teary-eyed over a sappy old sentimental song and an hour later expound to his sales staff on the subtle differences between French and English hookers. He was perhaps the perfect specimen of the cigar-chomping record man of the mid-20th century who changed American music, and, in turn, changed the world.”

For all his keen musical instincts and usual willingness to give producers Bass and Glover free rein to follow theirs, he had his blind spots — especially with James Brown, whose sales kept the company afloat in its final years. He thought “Please Please Please” was garbage until the money came in, and he adamantly opposed recording Brown’s 1962 “Live At The Apollo” (the label’s top-selling album) until Brown offered to finance it himself.

Time was running short for Nathan anyhow. He died March 5, 1968, of heart problems worsened by pneumonia. He was 64. Country-oriented Starday Records bought the company seven months later. Tennessee Recording and Publishing (whose owners included songsmith team Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller) held the label from 1971 to 1975, when it sold the master recordings, but not the publishing rights, to Nashville-based GML Inc. (owner of Gusto Records) which has kept much of the back catalog in print (www.gustorecords.com. In England, Ace Records (www.acerecords.co.uk) also delves deeply into King’s vaults. Heightening the authenticity, King/Gusto CDs often preserve the original cover art. In the “Battle Of The Blues” compilation series, Vol. 4 — featuring Harris, Roy Brown and Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson — the cover shows two attractive black women in high heels, bathing suits and boxing gloves, with one smiling happily at the camera as the other lands a punch on her cheek.

The apex of the reissues is the four-CD “The King R&B Box Set,” which is laden with hits and obscurities. It closes with three 1950s tapes of Nathan at company meetings, regaling his crew in his inimitable fashion and even labeling Harris a “stupid drunk” as he relives their contract negotiation session.

Dave Alvin said in the foreword to Fox’s “King Of The Queen City,” “Although independent record labels of that era (such as Sun, Chess, Modern, Imperial and Specialty) also recorded a variety of styles of urban and rural folk music, none of them recorded such a wide spectrum of styles as commercially and artistically successfully as King did. You could even make a decent argument that King was one of America’s great folk music labels.

The evolution of urban and working-class folk music documented over the history of King Records (whether intentional or not) captures the pivotal transition of the music from acoustic to electric, small town to big city, regional to national to international.”

Alvin further lauded the label’s incredible diversity.

“A case could be made that if your record collection consisted only of King Records, you’d have a damn good overview of post-World War II American roots music.”